The Living Archive That Adorns Morocco’s Greatest Moments

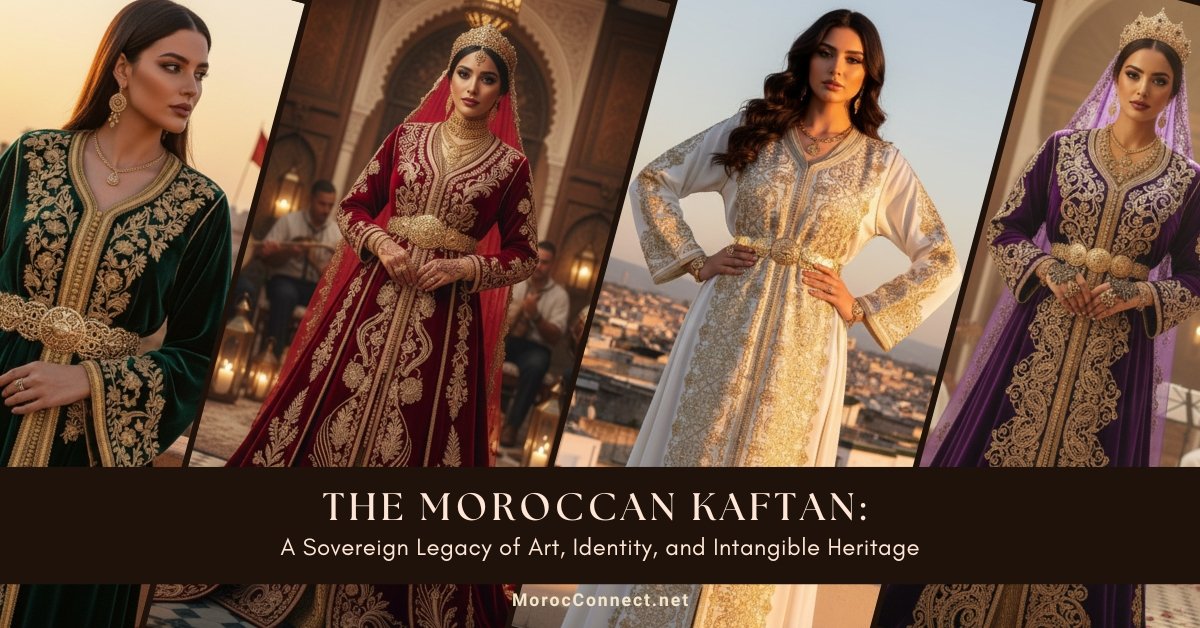

In December 2025, the Moroccan Kaftan achieved what few garments ever will: official recognition by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. But this is not merely a ceremonial accolade. It is a global declaration—witnessed by 195 nations—that the Kaftan is no ordinary dress. It is a textual archive. A sovereign creation. An eight-century conversation between artisans, dynasties, and the spirits of their ancestors, stitched into silk, velvet, and the incalculable hours of human devotion.

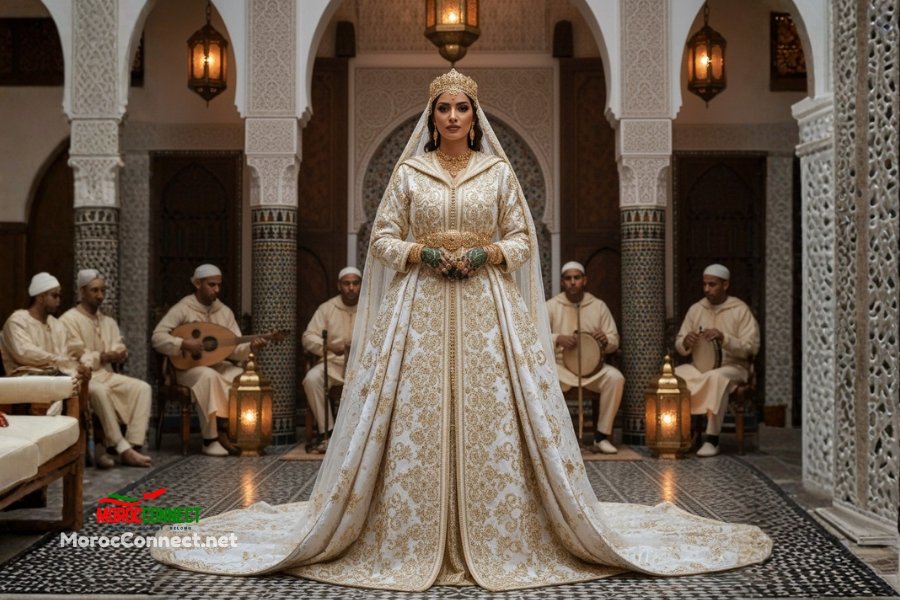

For a bride preparing for her wedding, the Kaftan is not clothing she wears—it is the vessel in which she enters one of life’s most sacred transitions. For the Maâlem (master craftsman) in a Fez atelier, it is not a product he sells—it is the culmination of forty years of knowledge passed from father to son, from master to apprentice, back through generations. For Morocco itself, the Kaftan is a statement. Not in words, but in thread, color, and the unmistakable silhouette that has announced Moroccan identity to the world for more than eight centuries.

This is the story of that legacy.

The Kaftan Is Moroccan. Not Ottoman. A Matter of Historical Sovereignty.

Here is where clarity is essential, because history is contested territory.

The Moroccan Kaftan is often conflated with Turkish or broader “Arab dress”—a conflation that dilutes Morocco’s distinctive contribution to world textile arts. The truth is more specific, more powerful, and entirely Moroccan.

The garment we know today was not imported wholesale from the Ottoman Empire or borrowed from Turkish fashion. Rather, it emerged through a distinctly Moroccan trajectory: first as a symbol of Moorish kingship, then refined through the courts of the Marinid dynasty, revolutionized under the Saadi sultanate, and perfected across the Alaouite era into the form we recognize today.

The Moorish Foundations: Power Robed in Tradition

The proto-Kaftan appears in the historical record far earlier than conventional histories suggest. Roman sculptures and historical inscriptions document the robes worn by Moorish kings—Bocchus I and Bocchus II—as long, straight garments cinched with distinctive belts. These proto-Kaftans were not accidental. They were intentional expressions of royal authority, signaling power, legitimacy, and cultural distinctiveness to neighboring kingdoms.

When Spain expelled its Jewish population in 1492 (the Alhambra Decree), it inadvertently gifted Morocco with some of the world’s finest textile artisans. These Sephardic refugees carried with them centuries of advanced knowledge: how to process silk threads, how to manipulate gold leaf into shimmering embroidery thread (skalli), how to execute the couching techniques that make Moroccan embroidery unmistakable. They settled in Tetouan, Fez, Chefchaouen, and Rabat—cities that would become the epicenters of Kaftan production.

This convergence—Moorish tradition meeting Spanish-Jewish technical mastery—created something entirely new. Not Ottoman. Not Arab in a generic sense. Moroccan.

The Marinid Codification: When Kaftan Became State Protocol

Between the 13th and 15th centuries, the Marinid dynasty transformed the Kaftan from an occasional luxury into a formalized element of statecraft. The Marinids built high-end weaving networks in Fez that specialized in the delicate silks, intricate dyes, and metallic threads that would become the Kaftan’s signature. They recruited master craftsmen from across the Mediterranean. They established court protocol that designated the Kaftan as official attire for judges (qadi), ministers, and diplomatic representatives.

The Kaftan, in other words, was institutionalized. It became the uniform of Morocco’s educated elite, the symbol of judicial authority, the announcement of one’s place within the Makhzen (royal court hierarchy). This was not incidental styling. This was statecraft through textile.

The Saadi Revolution: From Elite to Accessible

The Saadi Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur (r. 1578-1603) made a calculated decision that would democratize the Kaftan forever. He introduced the Al-Mansouria—a revolutionary two-piece garment featuring a Kaftan worn beneath an ornate outer dress. This innovation did more than create a new silhouette; it created a new market.

Suddenly, wealthy merchants and artisans could access Kaftan elegance without claiming royal lineage. The Kaftan descended from the palace into the city, from the ceremonial into the everyday. Yet simultaneously, the most elaborate versions remained reserved for weddings and religious observances—a distinction that persists today.

Al-Mansur’s choice was deliberately political. Spanish emissaries reported him wearing “white clothes in the Moroccan style” with a turban—explicitly rejecting Ottoman dress codes to assert Saadi independence and cultural distinctiveness. The Kaftan became not just fashion, but sovereignty. A textile declaration of non-Ottoman identity.

The Alaouite Refinement: From Then Until Now

The Alaouite dynasty (1631 to present) continued this trajectory, refining the Kaftan’s cut, elevating its embroidery, and gradually repositioning it as the primary festive garment for Moroccan women. By the 19th and 20th centuries, a bride’s Kaftan had become the centerpiece of wedding ceremony—worn and reworn across multiple celebration days, each color and style choice communicating her family’s status, her cultural region, and her personal elegance.

This historical arc is critical: The Moroccan Kaftan evolved through eight centuries of indigenous development. It absorbed influences—Andalusian techniques, Ottoman silhouettes (selectively), contemporary design sensibilities—but it remained fundamentally, unmistakably, Moroccan in its sovereignty and identity.

The UNESCO inscription of December 2025 codifies this historical reality. It is not a gift to Morocco. It is recognition of what Morocco has always known.

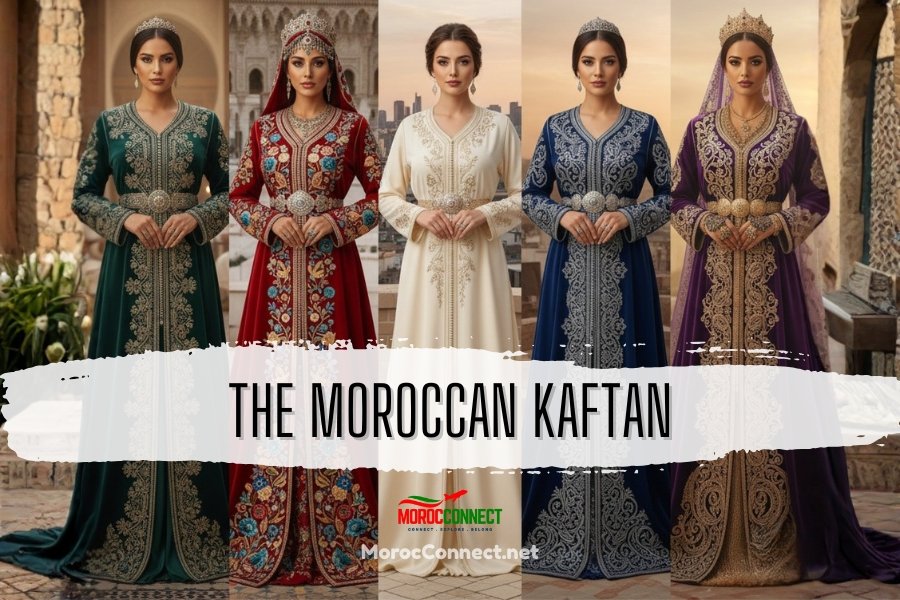

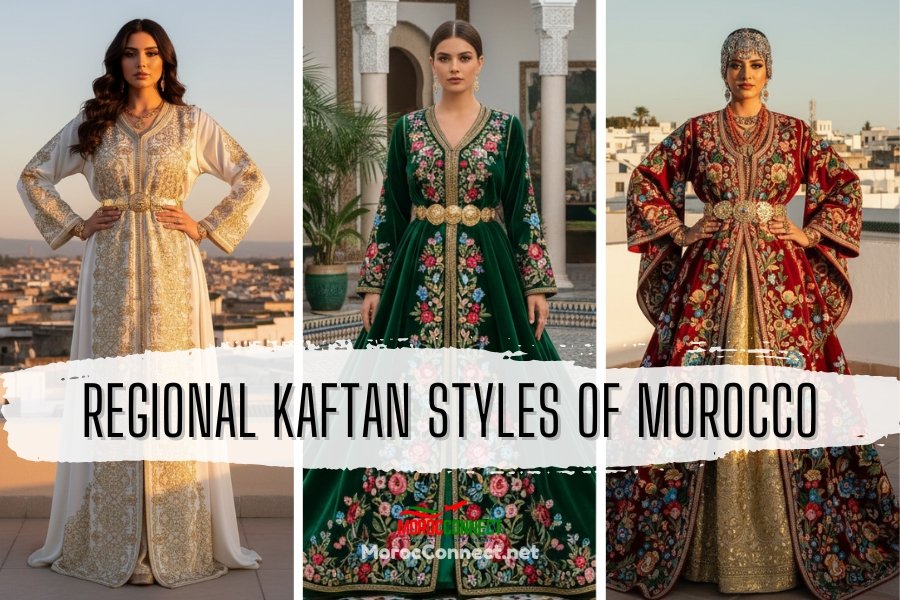

The Regional Schools: Three Distinct Dialects of Excellence

To understand the Kaftan’s depth, one must understand that there is no single Moroccan Kaftan. There are schools. Traditions. Geographic dialects of style, each reflecting the history, cultural influences, and artistic sensibilities of its city of origin.

These are not minor variations. They are fundamentally different aesthetic and technical approaches—the Moroccan equivalent of comparing Florentine Renaissance art to Venetian, or Burgundian Gothic to Parisian.

The Fassi School: The Language of Refinement and Reversible Mastery

Fez—home to Al Quaraouine University (859 CE), the world’s oldest continuously operating institution of higher learning—developed the most technically demanding embroidery tradition in the Islamic world. The Fassi Kaftan, executed in the Tarz El Ghraz (literally “target embroidery”), is a masterclass in restraint, precision, and optical illusion.

The Signature Technique: Couching as Spatial Reasoning

Imagine a gold thread. Now imagine holding that thread in precisely the correct position while a stronger thread locks it down with tiny, invisible stitches. The result: the gold appears to float on the surface, creating dimensional depth on a flat fabric. But here is the extraordinary part—the back of the embroidered area looks identical to the front. No knots. No loose threads. No visible construction. Just perfect, mirrored pattern on both sides.

This is not merely technical skill. This is three-dimensional spatial reasoning translated into textile form. A Fassi embroiderer must imagine the pattern as a physical object, understanding which threads carry which loads, how light will move across surfaces, where the eye will naturally rest. The couching technique demands this imaginal precision.

Visual Character: Delicate, Luminous, Understated

A Fassi Kaftan in a room is quiet. Not because it lacks presence, but because it understands the power of suggestion. The embroidery typically employs monochromatic gold or silver thread on heavy, jewel-toned fabrics—emerald green, sapphire blue, burgundy red, occasionally white for bridal wear. The motifs are geometric and restrained: teardrop shapes, concentric circles, floral arabesques inspired by Islamic design principles.

The embroidery concentrates in strategic areas—the chest, down the front button closure, along sleeves and hem—leaving large expanses of plain fabric that allows the eye to rest and the fabric’s own luxurious texture to speak. This is the opposite of maximalism. It is confident minimalism. A woman wearing a Fassi Kaftan signals: I understand beauty. I do not need to shout.

The fabric itself is typically of exceptional quality—silk velvet, often sourced through historical Mediterranean and Saharan trade routes. When light strikes the velvet, it creates a subtle luminescence. When the woman moves, the embroidery catches light and glimmers. The overall effect is ethereal elegance.

Historical Lineage: From Al-Andalus to the Makhzen

The Fassi school perpetuates the legacy of Andalusian-Jewish artisans who arrived after 1492, bringing with them advanced metallic thread techniques developed over centuries in medieval Spain. These artisans and their descendants created a synthesis: Moorish design sensibilities meeting Spanish technical precision. By the 17th century, Fez had become the global reference point for refined embroidery—a reputation that has never diminished.

The most expensive contemporary Kaftan designs in the world are still Fassi. Haute couture houses including Yves Saint Laurent have explicitly studied and honored Fassi techniques. The legendary designer spent years in Marrakech and Fez, absorbing the grammar of Moroccan textile arts before translating them into his own haute couture collections.

Wearing the Fassi Kaftan: A Declaration of Cultural Literacy

A woman choosing a Fassi Kaftan for her wedding is making a cultural statement. She is signaling respect for tradition, understanding of refinement, and confidence in understated elegance. This is the Kaftan of intellectuals, judges, and women from historic merchant families. It speaks softly, but it speaks with authority.

The Tetouani School: Drama, Color, and Andalusian Memory

Where Fez whispers, Tetouan sings.

Perched on Morocco’s northern coast, Tetouan developed a fundamentally different aesthetic vision. The city’s position as a gateway between Morocco and Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) created a unique cultural synthesis that manifests in the Tetouani Kaftan and, most spectacularly, in the Chedda—the traditional ceremonial dress of unparalleled magnificence.

The Chedda: A Theatrical Masterpiece

The Chedda is not a simple garment. It is an ensemble—a multi-layered composition of extraordinary visual complexity:

- The inner Caftan of Khrib: a luxurious base kaftan in fine silk or brocade

- The outer Chedda proper: an ornate, dramatically flared overdress in velvet or richly patterned fabric

- Seroual: embroidered pants worn underneath, visible at the ankles

- Bed’iyah: an embroidered vest that adds another layer of pattern and texture

- Jewelry, traditional tiaras, and ornate mdamma (belt) completing the ensemble

When a Tetouani bride stands in full Chedda regalia, she is transformed. The dramatic flare from the waist, the wide three-quarter-length sleeves creating theatrical movement, the riot of color and pattern—together, they create an effect of regal authority. She is no longer simply a woman in a dress. She is a crowned presence, a walking manifestation of her family’s cultural pride and artistic sophistication.

The Embroidery Language: Multicolor Boldness

Unlike the monochromatic restraint of Fassi work, Tetouani embroidery embraces color. Bright reds, golds, blues, and greens create vibrant geometric and floral patterns that cover substantial surface areas. The motifs often resemble stylized daggers (khanjar) or complex botanical forms—pomegranates, roses, carnations—rendered in interlocking geometric arrangements.

The embroidery demands attention. It is not content to be discovered through careful observation; it announces itself boldly. This reflects Tetouan’s historical self-confidence as a cosmopolitan port city with direct connections to the Mediterranean, to Al-Andalus, to global trade networks. The Tetouani woman wears her aesthetic—and her city’s—visibility as a point of pride.

Andalusian Echoes: A Living Archive

The Tetouani style directly perpetuates design elements from medieval Al-Andalus. When the Inquisition drove Muslims and Jews northward across the Strait of Gibraltar, they carried with them a visual vocabulary developed across eight centuries of Iberian Islamic civilization. The Chedda’s elaborate surface embellishment, flowing silhouettes, and use of rich, jewel-toned colors parallel the robes documented in medieval Spanish manuscripts.

In this sense, the Tetouani Kaftan is more than Moroccan fashion. It is living history. Every stitch carries memory of a civilization that once flourished in Spain, was forcibly expelled, and found refuge and rebirth in northern Morocco. The garment transforms that historical rupture into visual beauty—a way of saying: We survived. We preserved. We continue.

The Bride’s Transformation: Theater as Tradition

A Tetouani wedding is a multi-day event, and the bride changes outfits throughout. But the Chedda remains the centerpiece—the moment when she emerges in her full regalia for the major celebration. The visual impact is deliberate. She is meant to command the room. She is meant to be gazed upon. She is meant to embody her family’s cultural authority and artistic sophistication.

This is not vanity. It is ritual. Theater serving sacred purposes. The bride’s visual magnificence is an offering to her family’s honor, to the celebration’s solemnity, to the historical continuum that she now joins as a married woman.

The Rbati School: Modern Elegance and Refined Tailoring

If Fez represents medieval refinement and Tetouan embodies Andalusian memory, Rabat—Morocco’s capital and seat of modern political authority—represents contemporary possibility.

The Rbati Kaftan, executed in Tarz Rbati, represents a deliberate aesthetic shift toward streamlined elegance and precise tailoring. It is the school of modern Morocco.

The Philosophy: Tailoring as Statement

The Rbati Kaftan is characteristically narrow and close-fitting, hugging the body’s natural contours rather than draping loosely in the voluminous style of Tetouan or the restrained elegance of Fez. This silhouette reflects modern sensibilities—the influence of contemporary fashion—while honoring traditional construction methods and embroidery expertise.

The garment is typically crafted from velvet or thick velour, fabrics that provide structure and allow the body’s shape to emerge. This is a radical departure from the Fassi approach (which emphasizes the fabric’s texture) and the Tetouani approach (which creates visual drama through volume). The Rbati Kaftan says: Look at the woman. The dress frames her, but does not obscure her.

Embroidery as Accent, Not Subject

Rather than covering large surface areas with dense patterns, Rbati embroiderers concentrate intricate gold stitching on the sleeves and hem—areas that frame and move with the wearer. The motifs are often geometric and precisely rendered, maintaining the restrained color palette of Fassi work while employing the technical precision of Tetouani artisans.

The result is understated sophistication. The embroidery is undeniably present—a Rbati Kaftan from across a room declares itself as hand-embroidered luxury—yet it does not overwhelm. It enhances. It suggests rather than announces.

Historical Development: Rabat’s Modern Identity

Rabat emerged as the seat of Morocco’s modern state apparatus in the 20th century. As Fez represented medieval Islamic scholarship and Tetouan embodied Andalusian heritage, Rabat stands as the symbol of contemporary Moroccan identity. The Rbati Kaftan thus represents an evolution—a bridge between traditional techniques and modern aesthetic preferences.

A woman wearing a Rbati Kaftan signals comfort with contemporary femininity. She is honoring tradition while refusing to be bound by it. She is claiming the right to reinterpret, to modernize, to make the Kaftan speak to her moment, not merely to inherited custom.

The Anatomy of Excellence: Where Every Stitch Tells a Story

The Moroccan Kaftan’s reputation for unparalleled quality rests not on single elements, but on the collaborative mastery of multiple specialized artisans. Understanding these components reveals why each authentic Kaftan represents hundreds of hours of human devotion and why the garment commands prices that can reach 50,000+ dirhams in haute couture contexts.

The Maâlem: Master Craftsman as Living Archive

The Maâlem—a term meaning “master” or “teacher” in Moroccan Arabic—represents the apex of Kaftan-making expertise. Unlike apprentices or journeymen, the Maâlem has typically dedicated 30 to 50+ years to understanding every dimension of Kaftan production: fabric selection, pattern design, embroidery execution, button integration, and final finishing.

The Maâlem functions as designer, quality controller, trainer, and custodian of tradition. His reputation determines his workshop’s standing. Clients commission directly from named masters, understanding that they are purchasing not just a garment, but the accumulated expertise of a lifetime.

Historically, the Maâlem role was exclusively male, learned through family apprenticeship beginning in childhood or adolescence. Contemporary Morocco has begun to expand this structure. Women now train as Maâlems in specialized institutions nationwide, though the craft remains male-dominated in traditional family workshops.

Morocco’s government operates 69 specialized training institutions across the nation, connecting nearly 10,000 companies with 60,000+ apprentices annually—46% of whom are women. This institutional formalization aims to preserve traditional techniques while democratizing access and supporting economic sustainability.

The relationship between Maâlem and client is intimate and consultative, not transactional. The master discusses the bride’s vision, her family’s aesthetic preferences, the cultural region’s traditions, her body’s particular proportions, and her family’s budget. Together, they make decisions about embroidery style (Fassi restraint? Tetouani boldness? Rbati modernity?), fabric selection, color choices, and ornamentation level. The Maâlem brings technical expertise; the client brings personal vision. The Kaftan emerges from their collaboration.

The Sfifa: Silk and Gold Braid as Signature Element

The Sfifa (also called Aamara)—a narrow decorative band typically 2-5 centimeters wide—is perhaps the most visually distinctive element of Kaftan design. Sewn along the front closure, neckline, sleeves, and hem, the sfifa essentially frames the garment, drawing the eye along its contours and creating visual coherence.

Historical Genesis: From Spain to Morocco

The sfifa tradition originates directly from the expertise of Sephardic Jewish artisans who arrived in Morocco following the 1492 expulsion from Spain. These artisans possessed sophisticated knowledge of silk processing, silkworm breeding, and metallic thread work developed and refined over centuries in medieval Iberia. They brought not just techniques, but an entire knowledge system—understanding which mulberry trees produced superior silk, how to hand-dye threads to precise colors, and how to manipulate gold leaf to create shimmering embroidery threads.

When these artisans settled in Fez, Tetouan, Chefchaouen, and Rabat, they became the foundations of Moroccan textile excellence. Their descendants and apprentices created the distinctive Moroccan embroidery traditions that persist today. In this sense, every sfifa honors centuries of Iberian Islamic culture, preserved and perfected in Morocco.

Technical Production: Craft Within Craft

Traditional sfifa production involves hand-dyed silk threads wound onto wooden bobbins using distinctive tension methods unique to Morocco. Gold leaf is applied through processes that artisans guard carefully as family or workshop secrets. In modern times, synthetic metallic threads (skalli thread) have become more common for practical and economic reasons, though traditionalists insist that authentic, luxury sfifa employs hand-processed gold-wrapped silk.

The Timodontes association, headquartered in Morocco, has become the global reference point for preserving sfifa production techniques. They work directly with women weavers in Fez and surrounding regions, promoting craft preservation while supporting artisan economic autonomy.

Visual Poetry: How Light Moves Across Thread

Sfifa ranges in color from pure gold to silver, copper tones, and multicolored combinations. When light strikes the threads—candlelight at a wedding ceremony, morning sun in a courtyard, the glow of celebration—they create a luminous effect. The sfifa essentially animates the Kaftan, transforming static embroidery into something that seems to shimmer and shift as the wearer moves.

This is not incidental beauty. This is intentional enchantment. The sfifa says: This dress has been touched by mastery. This woman honors the occasion enough to wear something that glows.

The Aakad: Handmade Buttons as Miniature Sculptures

The Aakad—cherry-shaped buttons that run vertically down the Kaftan’s front closure—represent one of the garment’s most labor-intensive and visually distinctive components. Running 15-25 deep depending on the garment’s length, each button is individually hand-woven, a process consuming 20-40 minutes per button.

Geographic Significance: Sefrou’s Gift to Morocco

The city of Sefrou—located in northern Morocco and famous for its annual cherry festival—emerged as the global center of Kaftan button production. In the mid-20th century, the Jewish community of Sefrou dominated this craft; after the 1960s immigration wave to Israel, Muslim neighbors inherited and expanded the tradition.

Today, Sefrou hosts approximately 20 women’s cooperatives dedicated to button production. The exemplary model is Amina Yabis’s Cherry Buttons Cooperative, established in 2000. Yabis’s organizational innovation—creating a cooperative structure that provides economic security while preserving traditional techniques—has become a model for artisan economic organization throughout Morocco.

The Production Process: Patient Precision

Button makers begin with a single-ply rayon thread (sourced from China, sometimes called “cactus silk”) in colors specified by tailors or customers. The artisan carefully wraps the thread around a small paper or cardboard base (approximately one inch square), moistening the paper with her lips to secure the thread. She then threads a needle with matching or contrasting colors and weaves intricate patterns onto the base, maintaining precise tension throughout.

This is not mechanical work. This is craft. The finished button must be uniform in size, maintain structural integrity through decades of washing and wearing, and visually harmonize with the Kaftan’s overall aesthetic. A single button may require an hour’s labor—yet artisans receive modest compensation. The cooperative structure exists specifically to improve this economic equation while maintaining quality standards.

Button Varieties: Botanical and Geometric Poetry

Different button designs carry specific names based on their appearance:

- Bstilla: Resembling the traditional pastry, featuring layered, folded appearance

- Semma: Inspired by embroidered slippers, featuring botanical motifs

- Shems: Representing the sun, featuring radiating geometric patterns

The design selection dramatically affects the Kaftan’s overall aesthetic. Bold, geometric buttons create visual drama and modernity; delicate filigree buttons underscore refinement and tradition. A Maâlem might specify particular button styles to enhance the intended visual effect.

Durability as Testimony to Craft

Artisans note that buttons made in the traditional Sefrou style can last 50-60 years, enduring numerous washings while remaining structurally sound. This durability—exceptional for such delicate components—reflects the meticulous craftsmanship embedded in even the smallest elements. A Kaftan button is not merely functional; it is a tiny masterpiece designed for permanence.

The Mdamma: The Belt as Ceremonial Object and Symbol

The Mdamma (also called Semta in some regional dialects) transcends the functional category of “belt.” It is a structured, often ornate object crafted from gold, silver, or fabric-wrapped rigid materials, featuring elaborate surface decoration and traditional symbolism.

Historical Significance: Wealth Made Visible

Historically, the mdamma held profound significance in marriage negotiations and dowry arrangements. For women from wealthy families, the mdamma might be crafted from pure gold, weighing 300-500 grams, ornamented with intricate engravings and embedded precious stones—rubies, emeralds, and sometimes pearls. The mdamma literally embodied a family’s wealth and a bride’s economic security.

In many cases, the mdamma remained the woman’s personal property even in cases of marital dissolution or widowhood—functioning as a form of financial autonomy in societies where women’s independent wealth was severely limited. The belt was literally a woman’s insurance policy, her security, her claim to dignity.

Design Elements: Symbolism in Metal

Contemporary and traditional maddammes feature elaborate surface decoration. The most significant is the fakrone—a flower or turtle design centered on the frontal panel. This symbol is believed to bring happiness and protection from the evil eye (ain), merging Islamic spiritual traditions with pre-Islamic Moroccan folklore.

The fakrone is not merely decorative. It is protective. A bride wearing a mdamma with a prominent fakrone is invoking ancestral protection, spiritual blessing, and the accumulated hope of her family and community.

Modern Interpretations: Democratic Access

Contemporary maddammes employ diverse materials. Traditional versions remain crafted from solid gold or gold-plated copper featuring intricate engravings. Modern interpretations feature fabric-wrapped rigid structures—the belt constructed with an internal support (metal or reinforced fabric), then covered in matching or complementary fabric coordinated with the Kaftan itself. This approach democratizes access while maintaining the mdamma’s visual and structural function.

The Worn Tradition: Silhouette and Presence

The mdamma is worn quite high on the waist—not at the natural waist or hipline, but elevated toward the rib cage. This placement creates the characteristic Moroccan silhouette: an elongated upper body transitioning to gathered, flowing fabric below. The aesthetic effect is simultaneously elegant, practical, and visually confident.

The mdamma serves essential structural purposes. The multiple layers of traditional Kaftans and Takchitas require a belt to define the waist, create visual proportion, and provide structure to flowing fabrics. Without the mdamma, the Kaftan loses its silhouette; with it, the garment’s elegance crystallizes. The belt transforms clothing into presence.

The Symbolism of Color: A Visual Language Rooted in Spirit

In Moroccan culture, color is never arbitrary. Every hue carries symbolic weight, rooted in Islamic tradition, cultural history, and the specific occasions that garments will commemorate.

Green: The Color of Blessing and Beginnings

Green is the most spiritually significant color in Moroccan tradition. It represents hope, fertility, growth, renewal—deeply connected to Islam’s sacred associations with paradise. The Qur’an describes paradise as perpetually verdant, eternally green. In Moroccan Islamic practice, green has become the color of spiritual blessing and divine favor.

For the bride: Green is the color of the Henna Night (Laylat al-Henna)—the ceremonial eve before the wedding when the bride undergoes ritual purification. She wears her green Kaftan as an invocation: May I enter marriage blessed. May I bear children. May my life flourish. The green Kaftan is not merely clothing; it is a prayer made textile.

For religious observance: Green Kaftans are worn during Eid celebrations and other significant Islamic occasions. The color announces that the wearer is honoring the sacred nature of the moment.

Gold and Yellow: The Colors of Prosperity and Divine Favor

Gold and yellow symbolize wealth, prosperity, celebration, and spiritual enlightenment. Gold-embroidered Kaftans or those featuring gold fabric accents are reserved for occasions requiring visual opulence—grand wedding ceremonies, royal audiences, important social gatherings where one’s family’s status must be visibly affirmed.

The association between gold and royalty extends back millennia. Moroccan sultans wore gold-adorned garments as manifestations of divine favor and political authority. To wear gold is to claim—respectfully, but unmistakably—a place of honor.

Red: Power, Passion, and Celebration

Red represents passion, power, energy, love, and celebration. Red Kaftans are historically worn during wedding festivities and festive occasions. However, red carries more complex associations than contemporary Western celebrations suggest. In pre-Islamic Moroccan tradition, red signified protection and power; in Islamic contexts, red represents the passion of faith—the burning love of the believer for God and community.

Red Kaftans, while common for celebrations, are less frequent for everyday religious observances than green or white. But when a woman chooses to wear red, she is signaling confidence, power, and joy.

Blue and Turquoise: Serenity and Moroccan Identity

Blue and turquoise evoke serenity, spirituality, and Moroccan cultural identity. The deep indigo blues of Moroccan textiles have historical significance—indigo was traditionally extracted from plants and created through elaborate dyeing processes controlled by master craftsmen. Turquoise, the color of coastal waters and the sky, represents protection and clarity.

Modern Moroccan identity has embraced these blues (particularly evident in Chefchaouen’s famous blue-painted medina) as symbols of Moroccan heritage and spiritual continuity.

White and Cream: Purity, Elegance, and Formal Solemnity

White and cream are associated with purity, elegance, and formal occasions. White Kaftans are worn during Eid prayers and other significant religious ceremonies. For weddings, white is increasingly common for modern brides, though traditional Moroccan weddings typically feature multiple color changes throughout multi-day celebrations, each color shift marking a transition in ceremony and meaning.

Cream or off-white represents sophistication and simplicity—the garment itself, rather than color, commands visual attention. A woman wearing a cream Kaftan with restrained embroidery is making a statement about confidence and taste: I do not need to shout. My presence speaks.

The Craft Ecosystem: 2.3 Million Artisans, One Living Tradition

The Moroccan Kaftan is not produced by isolated artisans. It emerges from an entire ecosystem of interdependent craftspeople, suppliers, designers, and business owners. Understanding this ecosystem is essential to grasping why the Kaftan matters not just culturally, but economically—and why its preservation is a national priority.

The Numbers: Scale and Significance

Consider these figures:

- 2.3 million artisans work in Morocco’s craft sector

- 7% of Morocco’s GDP is generated by craft production

- 6 billion dirhams in annual revenue flows through traditional crafts

- 69 specialized training institutions operate nationwide

- 60,000+ apprentices enroll annually in these institutions

- 46% of apprentices are women—a significant shift from historical male-only apprenticeship patterns

- 10,000+ companies are connected to artisan networks

These are not marginal figures. These are structural. The Kaftan and its ecosystem constitute a major economic force, sustaining entire communities and preserving knowledge systems that might otherwise disappear.

The Training Pipeline: Formalizing Knowledge Transmission

Historically, Kaftan-making knowledge was transmitted exclusively through family apprenticeship. A son learned from his father. A daughter learned from her mother. Knowledge existed only in embodied practice—in muscle memory, in the eye that recognizes quality, in the hands that know precisely how much pressure to apply when couching gold thread.

This system created profound continuity but was also vulnerable. If no family member chose to become an artisan, knowledge risked disappearing forever. The Ministry of Culture recognized this vulnerability and has systematized training through institutions like the Training and Qualification Center in Marrakech and 68 additional facilities nationwide.

These institutions formalize what was historically tacit knowledge. Students learn not just how to execute techniques, but why—the principles underlying the craft. They interact with multiple masters, learning diverse approaches rather than a single family method. They receive certification that provides market legitimacy and access to business support programs.

The results are measurable: artisans participating in government support programs report income increases approaching 10%, and 45% report significantly increased sales.

Economic Vulnerability and Resilience

However, the statistics also reveal fragility. During pandemic disruptions (2020-2021), approximately 35% of tourism-dependent craft businesses permanently closed. The Kaftan industry relies substantially on wedding season demand and tourism—both vulnerable to global disruptions.

This reality underscores why the UNESCO recognition matters pragmatically, not just symbolically. International legal protection for the Kaftan as Moroccan Intangible Cultural Heritage creates:

- Market legitimacy: Authenticity certification becomes enforceable internationally

- Tourist confidence: UNESCO recognition attracts heritage tourism specifically seeking authentic, traditionally-made items

- Diplomatic protection: Nations and corporations cannot claim Kaftan production without facing international legal challenges

- Knowledge preservation: UNESCO recognition justifies government funding for training programs and documentation efforts

The UNESCO inscription thus serves as economic insurance for an entire sector.

The Caftan du Maroc Fashion Show: When Tradition Meets Contemporary Couture

Since 1996, Femmes du Maroc magazine has organized the annual Caftan Fashion Show—an event that has become the definitive platform for reinterpreting and elevating the Kaftan within contemporary haute couture contexts.

Economic Impact: From Workshop to Runway

The fashion show generates substantial economic activity. Haute couture Kaftans presented at the show cost 50,000+ dirhams to produce. Each annual edition features approximately 120 designs. The show’s impact ripples through the entire craft supply chain: embroiderers receive commissions, button makers work overtime, fabric suppliers increase orders, jewelry artisans craft complementary pieces.

The show’s publication in Femmes du Maroc magazine reaches international audiences, creating global awareness of Moroccan Kaftan design and attracting international buyers willing to pay premium prices for authentic pieces.

Creative Reinterpretation: Innovation Within Tradition

The fashion show provides a legitimized space for designers to innovate while respecting traditional foundations. Contemporary presentations have featured:

- Asymmetrical hemlines revealing layered silhouettes

- Integration of modern fabrics blended with traditional embroidery

- Minimalist interpretations of classical embroidery patterns

- International designer participation (the 2025 edition featured 12 foreign designers alongside Moroccan talents)

- Fusion experiments: corsets integrated with traditional Kaftans, Kaftan elements combined with contemporary silhouettes

- Sustainability focus: upcycled fabrics, eco-friendly dyes, zero-waste construction techniques

Designers are encouraged to “innovate while respecting the soul of the garment”—a formulation that acknowledges the Kaftan’s spiritual and cultural dimensions alongside its aesthetic function. The result is not cultural dilution but creative evolution. The Kaftan remains recognizably Moroccan while speaking to 21st-century sensibilities.

Cultural Messaging: The Kaftan as Statement of Agency

The fashion show explicitly positions the Kaftan as a symbol of Moroccan women’s agency, creativity, and cultural pride. Unlike Western fashion shows emphasizing novelty and seasonal trends, the Caftan show anchors innovation within cultural continuity.

Designers present not as individuals seeking fame, but as custodians of tradition. The runway becomes a stage not for ego, but for cultural responsibility. This messaging resonates powerfully with international audiences—particularly diaspora Moroccan women seeking ways to honor their heritage while claiming contemporary identity.

The Diaspora Dimension: Heritage as Portable Identity

For second and third-generation Moroccan diaspora communities living in Europe, North America, and the Middle East, the Kaftan has acquired profound psychological and cultural significance.

Diaspora women describe wearing the Kaftan as “coming home”—even when home is Paris, Montreal, or New York. The garment offers an accessible gateway to cultural identity, allowing diaspora members to honor their heritage without requiring linguistic fluency or extended time in Morocco. A woman wearing a Kaftan announces: I am Moroccan. I carry this heritage with me.

This diaspora market has created new economic opportunities. Boutiques and ateliers catering to diaspora clients have proliferated in European cities and North American metropolitan areas. Simultaneously, concerns about cultural appropriation have intensified. The UNESCO recognition provides diaspora communities with stronger tools to contest inauthentic or exploitative commercialization while supporting authentic artisan production.

The Kaftan’s role in diaspora communities has also influenced its evolution within Morocco. Young Moroccan designers now consciously create pieces that appeal simultaneously to tradition-focused domestic markets and to diaspora audiences seeking contemporary interpretations. This dual market has pushed the aesthetic boundaries of Kaftan design while maintaining essential traditional elements.

Glossary of Essential Terms

Understanding these Moroccan Arabic terms enriches engagement with the Kaftan and signals respect for its cultural context:

Kaftan/Qaffan (قفطان): The traditional single-piece Moroccan robe

Takchita (تكشيطة): Two-piece ceremonial ensemble (inner and outer garments)

Tahtiya (تحتية): Inner dress/foundation layer of Takchita

Fouqia/Dfina (فوقية/دفينة): Outer elaborate over-dress of Takchita

Chedda (الشدة): Traditional Tetouani ceremonial dress, characterized by dramatic flair and multicolor embroidery

Sfifa/Aamara (سفيفة): Decorative silk/gold braid trim

Aakad (لعقاد): Cherry-shaped handmade buttons

Mdamma/Semta (مضمة/صمطة): Traditional ornate belt, historically significant in dowries

Maâlem (معلم): Master craftsman; the highest level of expertise in Kaftan production

Seroual (سروال): Embroidered pants worn beneath Tetouani Kaftans

Bed’iyah (بدعية): Embroidered vest worn with formal Kaftan ensembles

Tarz El Fassi (الطرز الفاسي): Fez embroidery style; monochromatic, geometric, reversible

Tarz El Tetouani (الطرز التطواني): Tetouan embroidery style; multicolor, floral, dramatic

Tarz El Rbati (الطرز الرباطي): Rabat embroidery style; modern elegant, geometric, restrained

Nekacha (نقاشة): Henna artist; plays ceremonial role in wedding preparations

Laylat al-Henna (ليلة الحنة): The Henna Night; ceremonial eve before wedding when bride wears green Kaftan

Moutard (مُخْمَل/قَطيفة): Velvet; luxury fabric highly prized for formal Kaftans

Ben Chrif (بن الشريف): Brocade; richly patterned luxury fabric featuring metallic threads

Fakrone (الفكرون): Flower or turtle symbol on mdamma belt, believed to offer protection and blessing

Why This Matters: The Kaftan as Living Answer to Globalization

In an era of fast fashion, standardization, and cultural homogenization, the Moroccan Kaftan represents something increasingly rare and precious: a garment that has successfully navigated modernization while maintaining cultural authenticity and spiritual significance.

The Kaftan is worn at the most profound moments of Moroccan life. A young woman preparing for her wedding spends months—sometimes years—working with a Maâlem to design her Kaftan. She will wear it for perhaps 8-12 hours across a single night of celebration. Yet she will treasure it for the rest of her life. She will show it to her children. She may someday pass it to a daughter.

This is not consumption. This is inheritance. This is meaning-making.

The 2.3 million artisans sustaining the Kaftan ecosystem are not producing commodities. They are maintaining a knowledge system, perpetuating techniques developed over eight centuries, preserving a visual language that communicates cultural identity and spiritual values. They are answering a fundamental human need: to mark significant moments with objects of beauty and meaning.

The UNESCO recognition of December 2025 acknowledges this reality at the highest possible level. It declares that the Moroccan Kaftan is not a product, but a heritage. Not a trend, but a tradition. Not a garment, but a text—one that scholars, designers, and cultural enthusiasts will study and celebrate for generations to come.

For Morocco, for the millions of artisans sustaining this craft, and for diaspora Moroccan women claiming cultural continuity across borders, the Kaftan represents exactly what UNESCO seeks to protect: intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

The Kaftan is sovereign. It is Moroccan. It is irreplaceable. And now—officially, internationally, legally—the world has acknowledged its magnificence.

Key Findings: Why You Should Care About the Moroccan Kaftan

8+ centuries of indigenous development: The Moroccan Kaftan is not an Ottoman import but a distinctly Moroccan creation that evolved through the Marinid, Saadi, and Alaouite dynasties

UNESCO recognition (Dec 2025): Official status as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity provides legal protection against cultural appropriation

Three distinct regional schools: Fassi (refined, monochromatic), Tetouani (bold, multicolor), and Rbati (modern, tailored) represent geographic dialects of style

2.3 million artisans: The Kaftan ecosystem sustains an entire economic sector, contributing 7% to Morocco’s GDP

Mastery embedded in every component: From the Maâlem’s design vision to the Aakad button maker’s precision, the Kaftan represents collaborative excellence

Living tradition, not museum piece: The Caftan du Maroc fashion show (since 1996) demonstrates that Kaftan-making continues to evolve while maintaining tradition

Spiritual and ceremonial significance: Colors (green for brides, gold for prosperity) and symbols (fakrone for protection) embed spiritual meaning in textile form

Diaspora significance: For Moroccan diaspora communities, the Kaftan serves as portable heritage—a way to claim cultural identity across borders

The Moroccan Kaftan is more than a dress. It is a declaration—of history, identity, artistry, and spiritual continuity. It is Morocco, wrapped in silk and gold, worn by millions, honored by the world.